Grading Beyond 4 Cs

Our eyes are most attracted to the brilliance, fire and scintillation of diamonds. People pay a lot of money, to make these stones, a part of their collection. With no real visible inclusions or flaws to the naked eye, it becomes pertinent that you ensure the price you have paid for the diamond is just and fair. Thanks to the 4C grading system, it became easier for the end consumer to trust the jeweller while buying the diamond.

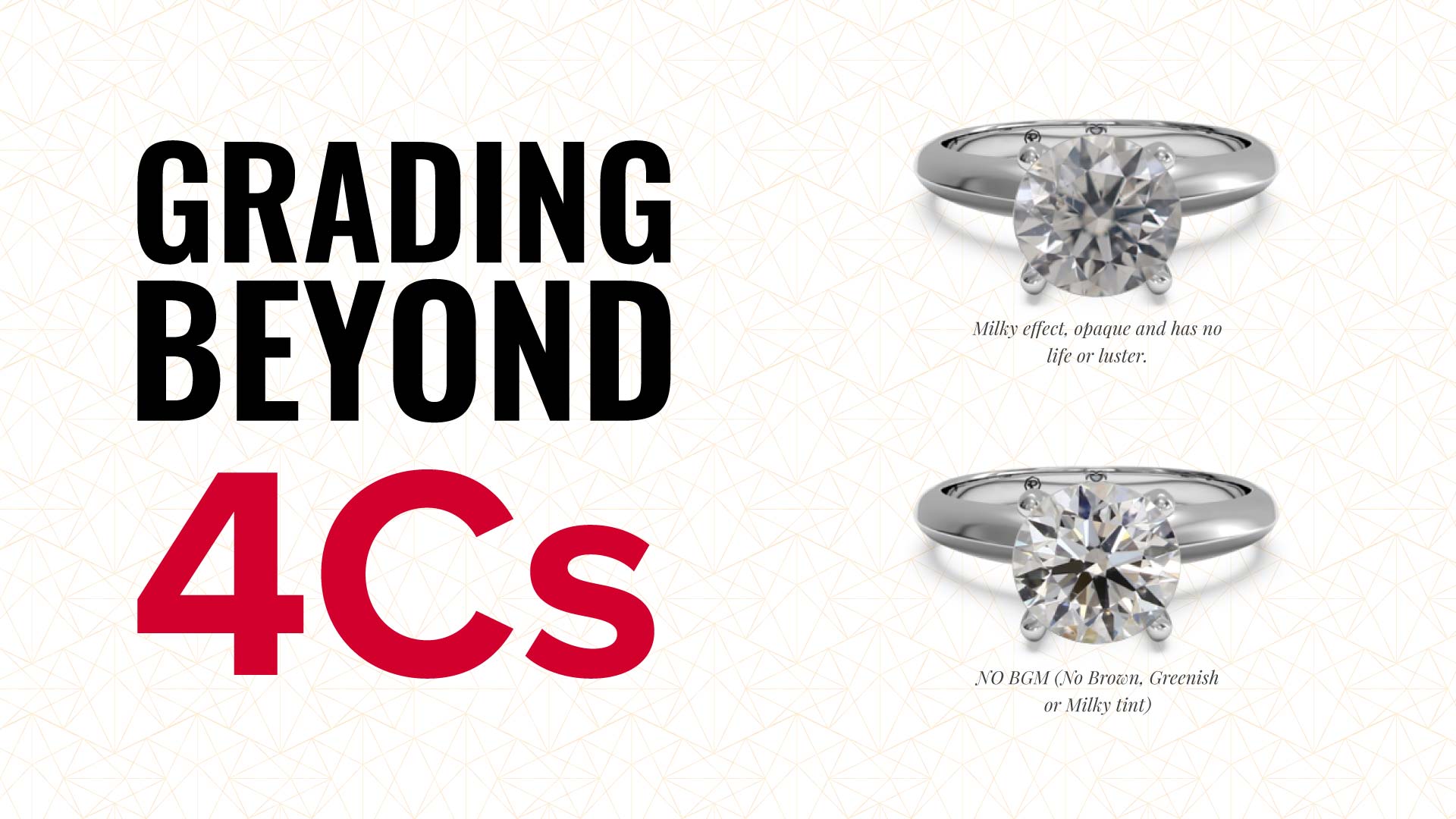

However, when it comes to trade, buyers consider a lot of other factors that go beyond the 4Cs. Trade often looks down upon diamonds that appear to have a milky appearance and/or a brown tint. A milky tone can make a D- Flawless diamond appear dull and lifeless, thus reducing the value of the diamond.

Both diamonds are graded exactly same E color, SI2 Clarity

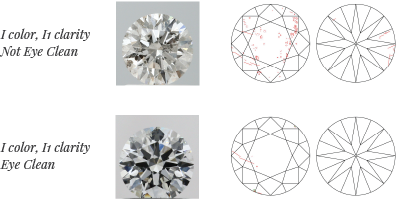

The issue of diamond clarity shares a similar conundrum. There isn’t a specific clarity grade that guarantees an eye-clean diamond. Due to the reflection of the inclusions by the pavilion facets, a good cut diamond may appear to have more inclusions. Making it appear darker than it actually is and reducing its value considerably.

Till now, a certificate alone was not enough to determine, whether or not a diamond was eyeclean. A buyer wanted to see the diamond physically and then determine the price. But to the seller this not only meant, transporting the diamond to the buyer for inspection and restricting the geography of their operation; but also depending on the buyer to set the discount.

The Curious Case of Fluorescence

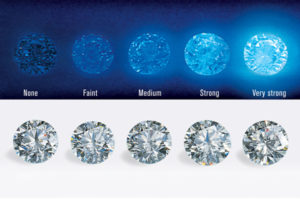

The diamond industry has a complicated relationship with fluorescence.

Historically, both the trade and consumers saw value in a diamond that has fluorescence under ultraviolet light. The perception was that it added to the color of the diamond while also providing various niche marketing opportunities. Take the ’80s disco era, when neon was in and a glow-in-the-dark diamond might have been cool.

But the positive view of fluorescence has changed over time — at least, from the trade’s perspective. Various periods of oversupply, and one or two scandals related to the subject, led the trade to discount diamonds with varying degrees of fluorescence. We explore this issue in the November issue of Rapaport Research Report and present our updated guidelines to what those discounts are. The higher the color, the more fluorescence negatively affects price.

The discounts are puzzling. The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) published a comprehensive paper on fluorescence in 1997, in which it challenged the notion that this trait had a negative impact on higher color diamonds. If anything, the GIA concluded, fluorescence adds to lower colors, and it does not affect a diamond’s transparency.

Most importantly, the GIA found that the jewelry-buying public saw no difference between diamonds with fluorescence and those without. It wasn’t an issue for the consumer back then, and it isn’t today, according to most of the diamond professionals we consulted for the report.

If that is true, the trade is missing out on an opportunity. The biggest challenge facing the industry is figuring out how to broaden demand, which has narrowed over the past decade as buyers have become more specific in their requirements. As a result, there is an oversupply of diamonds that are difficult to sell. In many cases, it’s because they are fluorescent goods.

We’re seeing a recovery in demand for stones with faint or no fluorescence, and continued weakness among diamonds in the medium, strong and very strong categories. That’s difficult to understand if the consumer isn’t too bothered about the issue.

And therein lies the opportunity: Savvy diamantaires and jewelers are buying fluorescent goods and marketing them as a specialized product. Some big sellers — most notably Alrosa — have a lot of fluorescence in their production and are trying to create a category for those stones. Considering that the industry needs an avenue for offloading its fluorescent diamonds, it should be encouraging initiatives like these.

To download the full report as a subscriber to the Rapaport Research Report, or to subscribe, click here.

Image: The GIA’s fluorescence scale, showing diamonds illuminated in natural light

and under a UV light. (GIA)

Do the 4Cs Still Make the Cut?

The “5Cs and 2Ts” isn’t as catchy as the usual formula, but it might be a better pricing method, according to the author of a diamond-trade guide that claims the 4Cs are no longer adequate.

“One of the biggest misconceptions is that there are only four diamond price factors — color, clarity, cut and carat weight,” Renée Newman, a graduate gemologist who last year published the third edition of her Diamond Handbook, says in an interview with Rapaport News. “In fact, there are other factors, such as the transparency and treatment status. They can have a large impact on price. We [in the trade] may know that, but the consumers don’t, because they just hear about the 4Cs.”

Transparency matters

The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) developed the 4Cs in the 1950s, when the industry considered cloudy diamonds to be industrial quality and didn’t put them into jewelry, the Handbook explains. Today, jewelers do use cloudy and hazy diamonds, but their clarity grades often don’t reflect their lower transparency, even though that characteristic can affect the value.

Newman distinguishes between clarity — a stone’s lack of inclusions and other blemishes — and the first “T,” transparency, which is how well it lets light pass. While a diamond with high clarity will have few or no inclusions, a stone is transparent if a viewer can see objects through it distinctly. Many laboratories don’t take into account subtle differences in transparency, Newman writes. “I’ve seen hazy and slightly cloudy diamonds with VS clarity grades,” she notes in the book.

How to treat treatments

Very few treated diamonds were on the market when the 4Cs came along, Newman explains. Most diamonds are still untreated now, but it’s becoming a larger minority as sellers seek to improve stones’ color, clarity and transparency.

This second “T” is important, as it hugely impacts the price. An untreated 1-carat, fancy-green, VS-clarity diamond will often fetch more than $200,000, compared with around $5,000 for an irradiated diamond with otherwise identical characteristics, Newman estimates. Treated diamonds are also much harder to resell.

A fifth “C” — and a sixth?

The “cut” part of the 4Cs needs to be two separate categories, she argues. In the 1950s, the trade didn’t differentiate between the shape and the quality of the cut when deciding prices, so it didn’t matter that the same term referred to both things. Now, the cutting style and shape are a distinct price factor from cut quality, with many labs providing a grade for the latter, she observes.

Meanwhile, rising interest in lab-grown diamonds has prompted Newman to consider an eighth criterion for a revised edition of one of her other books aimed at consumers.

“I left out a ‘C’ that I’m going to add when I redo my Diamond Ring Buying Guide, and that is the creator. Is the creator man or nature?”

Hard to change

Newman is not trying to get traders to discard their 4Cs charts, as the system is so ingrained, she notes. But they should be aware of the additional elements affecting the value of a diamond. That’s why she emphasizes the 5Cs and 2Ts in the Handbook.

“They can’t just completely change over all their advertising and all the materials they have, so I don’t expect people to change the 4Cs. But I do expect them to understand all the price factors,” she concludes.

Image: Renée Newman. (Renée Newman)